Note: this tutorial covers scraping pollen counts from the BBC site; this data only appears on the BBC site in the summer so you might not be able to find it, depending on the time of year you're reading this!

Further note: the original site is no longer online as of 2020.

Having suffered from hayfever for a long time, none of the pollen count sites I came across were much use. I decided to create my own - just a site with today's pollen count and as little else as possible, and that's what we'll be creating in this tutorial.

The site's setup is incredibly simple - there's one HTML page which displays data, and a backend API which generates the pollen count data. We'll be using the following technologies to make the site:

Make sure you install these before we start!

Setup

To begin with (after installing the above dependencies), we need to set up an Express project. In a new folder, create package.json and add the following:

// package.json

{

"name": "pollencountsite",

"version": "1.0.0",

"private": "true",

"description": "Scrape current pollen count",

"main": "server.js",

"author": "[ you ]"

}Save this file, then open the terminal and run npm install in this folder to install all your dependencies. You can also create this file from the command line by running npm init and answering the prompts there.

Backend

The backend needs to have two functions: generate the pollen count data and serve our frontend files. The first step is to generate the data to display; when I built the site, I couldn't find any APIs which provided pollen count data, although I've since found the Met Office API which requires signing up and then contacting them.

Since I wasn't aware of this API at the time, I decided the best option was to scrape the data from the BBC weather site once a day, then use that as my data. There's a few problems with this approach: scraping is a bit of a grey area, and not all sites are happy for you to scrape them. We're only going to be scraping the site once per day, so we're not abusing the BBC site, although if they ask you to stop then do so!

The other problem with this approach is that the BBC pollen count is only available for one area at a time, and the URLs are not easily-modifiable (i.e. the URL is a string of numbers rather than a city or area, so it's not easy to work out how to change the area you're getting data from). This seemed an acceptable trade-off to me - this is a very basic site! - so all my data is based on the pollen count for Bristol. Now I'm aware of the Met Office API, I'll probably update this at some point to have the correct data for the user's location.

So, the short version: our site will run on Heroku, scrape data from another site, save it to a JSON file on Amazon's AWS S3 service, then display it to the user.

Right then, on to the code! We'll need to install a few dependencies to run the site, so run the following to install them:

npm install --save express

npm install --save request

npm install --save cheerio

These commands install the Express, Request and Cheerio modules and tell our application that we require these to be installed for our site to work. The great thing about package managers like NPM is that you just need to list anything your site needs to work, then you can move your code to a different machine and simply run the install command, and your site will be able to work! If you look in the package.json file, you'll see that it now has a 'dependencies' object:

// package.json

"dependencies": {

"cheerio": "^0.17.0",

"express": "^4.7.2",

"request": "^2.39.0"

}which is the list of everything the site requires to run. There is also now a folder in the root directory called node_modules, which is where the files for the dependencies are installed. Since this folder can be huge (depending on how many modules you have installed), it's a good idea to exclude it from source control - if you want to work on the site on another machine, simply run npm install and all the dependencies will be set up automatically.

To ignore the node_modules folder in Git, create a file called .gitignore in the root folder, and add the following line:

node_modulesWe'll now save everything into source control so we have an easy way to roll back any changes - in the root folder run

git init

git add -A

git commit -m "Setting up dependencies"

If you have a Github account, now's the time to set up a repo and push to it so you have a remote copy of your site.

This is a simple site, so all of the backend will be in one file: server.js in the root folder.

Add the following code:

// server.js

// load all our modules

var express = require("express");

var request = require("request");

var cheerio = require("cheerio");

// set the port the server will run on

// if it's not set as a variable, it'll run on port 3000

var port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

var app = express();

app.use(express.static(__dirname + "/public"));

app.get("/", function (req, res) {

res.render("index"); // this serves the frontend of the app

});

app.get("/scrape", function (req, res) {

// this is where we'll do all the scraping

});

app.listen(port);

console.log("Listening on port " + port);

exports = module.exports = app;Create the frontend

app.use(express.static(__dirname + '/public')); tells Express to look in a folder called public for all static files to serve. The following code tells Express to look for a file called /public/index.html when someone requests the root of the site (ie the homepage):

// server.js

...

app.get('/', function(req, res) {

res.render('index');

});

...Create a folder called public in the root of your app - this will contain all the frontend code for the site. In the public folder, create an index.html file, which will be served as the homepage, and folders for JS and CSS:

app/

|-public/

| |-css/

| |-js/

| |-index.html

|-server.js

|-package.json

Edit the index.html file so we've got a basic layout:

<!-- index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Today's Pollen Count</title>

<meta name="description" content="My lovely pollen count site" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/css/main.css" />

</head>

<body>

<main class="main">

<p>Today's pollen count is</p>

<h1 class="mega"></h1>

</main>

<script

defer

src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.1/jquery.min.js"

></script>

<script defer src="/js/main.js"></script>

</body>

</html>Create the main.css file in the CSS folder, and add the following basic styles:

/* main.css */

body,

html {

background: #e5137a; /* hot pink */

}

.main {

width: 80%;

margin: auto;

color: white;

text-align: center;

}

.mega {

font-size: 3em;

}(the full Sass source code is on the Github repo if you want something a bit fancier).

The <h1 class="mega"></h1> tag is where we'll display the pollen count - we'll load the data through AJAX and add it to the H1 tag. However, we don't have this data yet, so let's get onto the scraping!

Scraping fun

Now we've got all the boring setup out of the way, let's implement the scraping part.

Update the server.js file so it looks like this:

// server.js

var express = require("express");

var request = require("request");

var cheerio = require("cheerio");

var port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

var app = express();

app.get("/scrape", function (req, res) {

// this is the BBC Weather site for Bristol

var url = "http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/2654675";

var json = { count: "" };

// the request module lets us open other sites

request(url, function (error, response, html) {

// make sure that there weren't any problems

if (!error) {

// cheerio allows us to interact with the opened site much like jQuery

var $ = cheerio.load(html);

// this is where we'll save the pollen count

json.count = "";

json.date = new Date();

// show what we've got so far in the terminal

console.log(json);

// this will appear on the site

res.send("Updated pollen count.");

} else {

// if there was a problem, display what it was

res.send(error);

}

});

});

app.listen(port);

console.log("Listening on port " + port);

exports = module.exports = app;You can now run the site by running node server.js in the terminal, then opening a browser to http://localhost:3000/scrape. If there were no errors, then you should see the message 'Updated pollen count' in the browser and a Javascript object in the terminal containing a blank count along with today's date.

Finding the data

We now need to find the data in the HTML we've scraped from the BBC site. Inspect the BBC Weather site and look for something unique surrounding the pollen data - in this case, the parent element has a class of pollen-count which doesn't appear anywhere else on the site, so we can use this to target the correct info.

// server.js

var express = require("express");

var request = require("request");

var cheerio = require("cheerio");

var port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

var app = express();

app.get("/scrape", function (req, res) {

// this is the BBC Weather site for Bristol

// replace this with the correct URL for your area

var url = "http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/2654675";

var json = { count: "" };

// the request module lets us open other sites

request(url, function (error, response, html) {

// make sure that there weren't any problems

if (!error) {

// cheerio allows us to interact with the

// scraped site much like jQuery

var $ = cheerio.load(html);

// we can now find the pollen data using Cheerio

json.count = $(".pollen-index .value").text();

if (!json.count) {

json.count = "Low";

}

json.date = new Date();

// show what we've got so far in the terminal

console.log(json);

// this will appear on the site

res.send("Updated pollen count.");

} else {

// if there was a problem, display what it was

res.send(error);

}

});

});

app.listen(port);

console.log("Listening on port " + port);

exports = module.exports = app;If you run node server.js again, you should now see the pollen count in the terminal!

Saving the data

We're going to run this site on Heroku, which is a great platform for deploying and running apps, and has a free tier as well :) However, you can't save local files on Heroku, so we'll need to save the JSON data on Amazon's S3 service (which also has a free tier). S3 is a cloud platform where you can store and access files, and we'll use this to store our pollen data JSON file and as a place to read this data in to display to users.

Sign up for an S3 account, then create a bucket (Amazon's name for a folder) which we'll use to save data in. S3 can be a bit confusing, and I don't want to go into too much depth here since I'll be here forever, but there are plenty of tutorials around which explain how to use it. Make sure you save your Access Key ID and Secret Access Key since we'll be using these to access our data.

Note: if you have any other accounts in S3, or are likely to in the future, it's good practice to create a new user with access only to this bucket. This is so if your details get compromised, attackers can't wipe your entire account, only an individual bucket.

When you've created a bucket, highlight the bucket and click on the Properties tab in the top-right corner. We need to update the permissions so we can save and read files from this bucket, so make sure your username has list and upload/delete permissions, then edit the CORS configuration so it looks like the following:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<CORSConfiguration xmlns="http://s3.amazonaws.com/doc/2006-03-01/">

<CORSRule>

<AllowedOrigin>*</AllowedOrigin>

<AllowedMethod>GET</AllowedMethod>

<AllowedMethod>PUT</AllowedMethod>

<AllowedHeader>Content-*</AllowedHeader>

</CORSRule>

</CORSConfiguration>This will allow any site to alter files if they have the correct username and password, so make sure you alter the AllowedOrigin line to just have your domain name. To allow localhost, you'll need to keep the AllowedOrigin set to '*' for now, but remember to alter this when you go live.

Got your Access Key ID and Secret Access Key handy? If not, find them, because we need them now to set our local environment variables - these will allow us to interact with our S3 bucket while running the site locally. Setting these variables depends on which OS you're running - for Windows, open Powershell and run

$env:AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID="[ your key here ]"

$env:AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY="[ your key here ]"

Make sure you include the double quotes around the key. If you're using OSX or Linux, open the terminal and run

$ export AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=[ your key here ]

$ export AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=[ your key here ]

These commands set variables on your machine which are used by the AWS SDK code to access your S3 bucket. When we come to deploy our app, you'll need to add these details to the production environment as well (I'll cover that in a bit).

Ok, code time! run npm install --save aws-sdk to install the AWS module which will allow us to interact with our bucket, then update server.js:

// server.js

var express = require("express");

var request = require("request");

var cheerio = require("cheerio");

var AWS = require("aws-sdk");

var port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

var app = express();

app.get("/scrape", function (req, res) {

var url = "http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/2654675";

var json = { count: "" };

request(url, function (error, response, html) {

if (!error) {

var $ = cheerio.load(html);

json.count = $(".pollen-index .value").text();

json.date = new Date();

console.log(json);

// s3 credentials set as environment vars process.env.AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID, process.env.AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

var s3 = new AWS.S3();

// the name of your bucket

var bucketName = "[ your bucket name ]";

// name of the file to save

var keyName = "pollen.json";

// set the parameters

var params = {

Bucket: bucketName,

Key: keyName,

Body: JSON.stringify(json, null, 4),

ACL: "public-read",

};

// and finally, write the file to AWS

s3.putObject(params, function (err, data) {

if (err) {

console.log(err);

} else {

console.log(

"Successfully uploaded data to " + bucketName + "/" + keyName,

);

}

});

res.send("Updated pollen count.");

} else {

res.send(error);

}

});

});

app.listen(port);

console.log("Listening on port " + port);

exports = module.exports = app;Run node server.js again and - hopefully - you will now see a JSON file appear in your S3 bucket! This is the part where I had most issues - if you can't write to the bucket then check your permission settings in AWS, make sure you've set your environment variables correctly, or look into the error logged in the terminal. Now, every time you go to the /scrape page of your site, you'll create a new JSON file and save it to AWS. This is the key part to automating the pollen data scraping - more on this later.

Hooking up

Now we've got our data saved to AWS, it'd be pretty handy to be able to display it to the user. Open public/js/main.js and add the following:

// main.js

$(document).ready(function() {

// find the URL of your JSON file on AWS - it'll be in your bucket

// and look something like https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/[bucket name]/pollen.json

// we load the JSON file using jQuery's AJAX

$.get([Your AWS pollen.json file])

// Once we have the data, we parse it to find the pollen count

.done(function(data) {

data = JSON.parse(data);

var pollen = data.count;

// update the <h1 class="mega"> with the pollen count

$('.mega').text(pollen);

}

// if we couldn't get the data from AWS, display an error message

.fail(function() {

$('.mega').text('Unknown');

$('.main').append('<p>Refresh to try again</p>');

})

.always(function() {

// if you're using a loading gif, this is where you'd hide it

});

}Hopefully this is fairly self-explanatory - we wait until the page has loaded ($(document).ready()), load our AWS JSON file ($.get()) and then update the page with the pollen count (.done()). If there was an error getting the JSON data from AWS, then this is handled in the .fail() function, and any tidying up we need to do is in the .always() function (if you wanted to hide a loading gif, then you'd do it there). Your JSON file URL should look something like https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/[Your bucket name]/pollen.json, depending on which AWS server you're using.

Now, if you run node server.js and open your browser to localhost:3000, you should see the pollen count loaded from AWS! If there are any problems, check the web developer tools in the browser (F12) to see if there are any errors - common problems include CORS restrictions (ie your JSON file on AWS hasn't been configured to allow your localhost domain to retrieve it).

Deploying

We're going to deploy our app to Heroku, so you'll need to sign up for an account (it's free!). Once you've signed up, install the Heroku Toolbelt which contains a command-line API for uploading and updating apps on Heroku. After installing, run heroku in the terminal to make sure everything's installed properly:

and then run heroku login, which will prompt you to enter your email and password, and will create a new public key if you don't have one already, allowing you to deploy the app from the terminal.

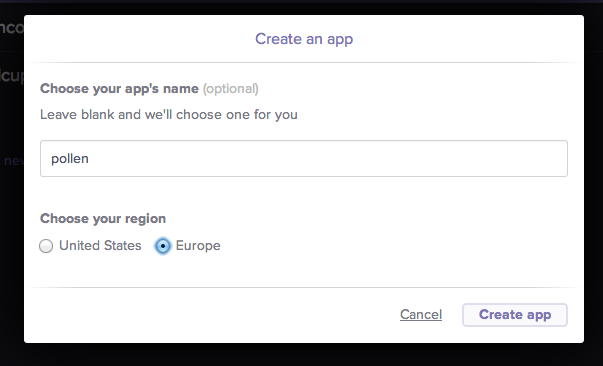

Now create a new app in Heroku - either through the Heroku site from the dashboard or via the terminal: heroku apps:create [your app name], then run heroku apps and make sure that your new app appears in the list. Commit everything in git:

git add -A

git commit -m "Added AWS integration"

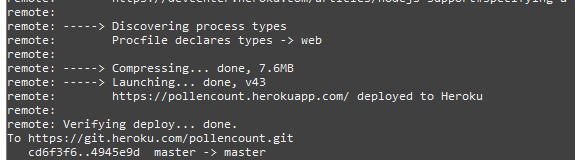

Back in the terminal, in the app folder, run heroku git:remote -a [your app name] This adds a Git remote branch on the Heroku server, which is used to push all your code to the live environment. Now, the moment of truth! Run git push heroku master, which will upload your code to Heroku, install any dependencies and start the server.

If everything went well, you'll be shown the live URL of your app in the terminal:

and then visit the site to check it's all working properly! You should see your pollen count on the homepage (if not, check for errors in the dev tools console and make sure that AWS has your Heroku domain added in the CORS policy). You'll need to make sure that /scrape gets visited at least once a day to keep your pollen count data up-to-date - you could set a cron job on a Raspberry Pi (which is what I do!), or there are various sites which ping URLs automatically.

Next steps

This is a fairly basic tutorial, so there are plenty of areas to improve:

- Scraping is inherently problematic for getting data: if the site you're scraping changes it's markup then it could break your scraper. In fact, the BBC site where I'm getting the data only shows pollen counts around May - September, so there is no source of data for the rest of the year! It'd be better to use a stable API, for instance the Met Office's, if they ever get around to opening access to it.

- This tutorial only contains very basic CSS, so there's loads of improvements to be made there.

- We haven't set any caching headers on the JSON file saved to AWS, so browsers won't cache it for as long as they could. This means that every time we load the page, we're requesting a new copy of the file even if it hasn't changed.

- Frontend performance could be improved by enabling Gzip, compressing the CSS and JS etc.